The genre of the self-portrait has a very specific place in the artistic canon. It is usually seen as a distinctive artistic ‘subset’ of the portrait, which is defined by the extent and character of the artist’s relationship to their subject. With the self-portrait, this connection is absolute – one and the same person is engaged in the closest possible dialogue with themself, thus giving us an intimate look at their private world and innermost thoughts.

The 20th century witnessed the significant expansion and modification of the approaches to self-portrait that we know from and can identify in historical eras. Scientific developments, changes in society and the rise of individual artistic self-awareness have provided artists not only with entirely new themes but also with new strategies of self-presentation and self-stylisation. Rimbaud’s maxim of ‘I am someone else’ marks an extreme way of approaching oneself and one’s work. It is an expression of the artist’s revolt against social conventions and represents an absolute demand for the ‘seer’ status of an artist engaged in the search for and exploration of themself, in transforming their perception and their thoughts.

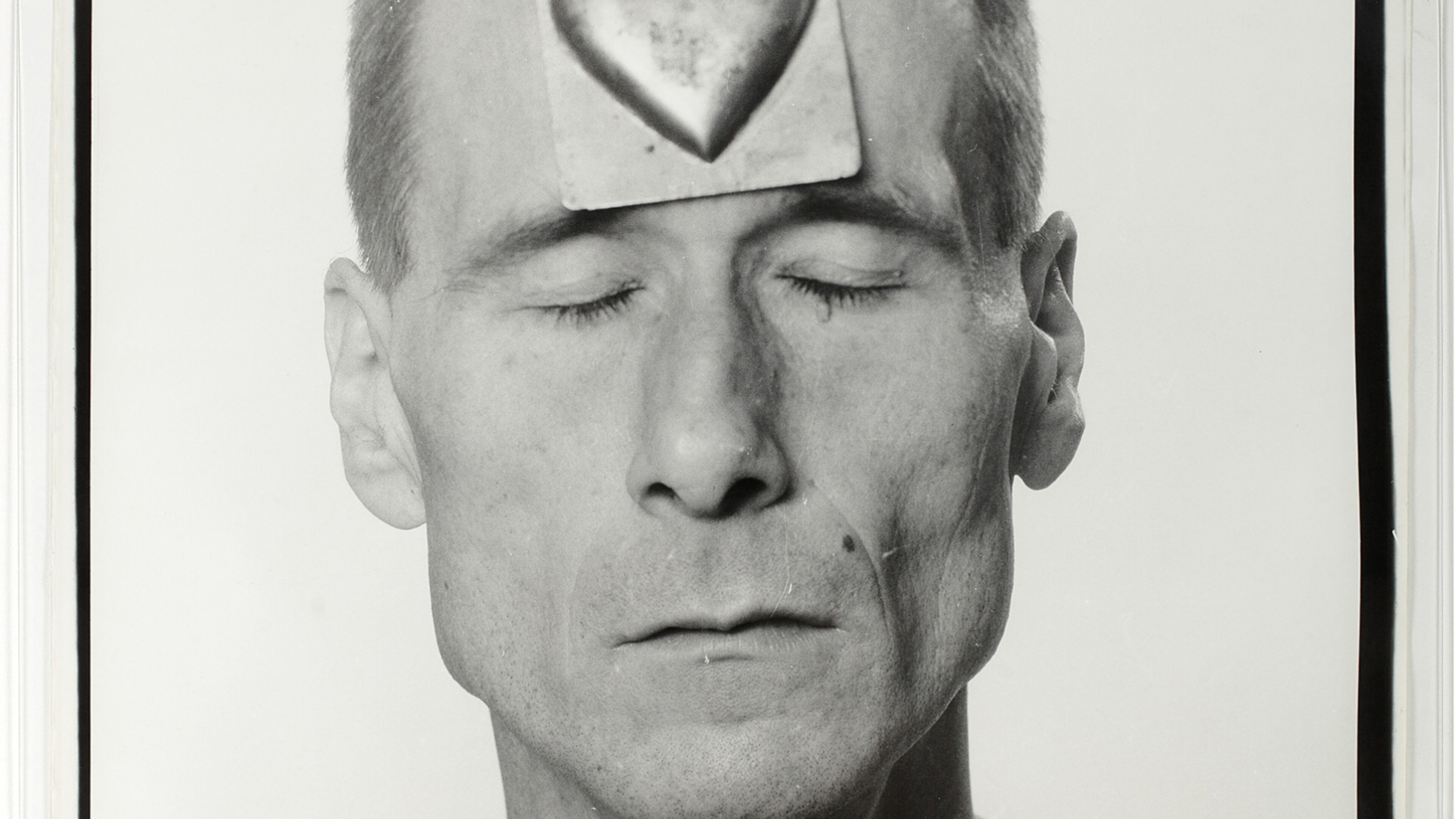

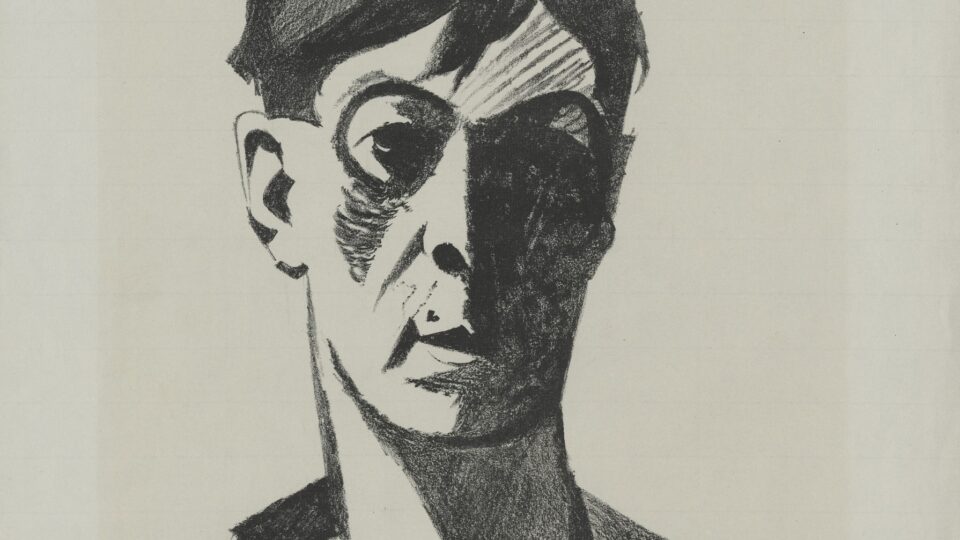

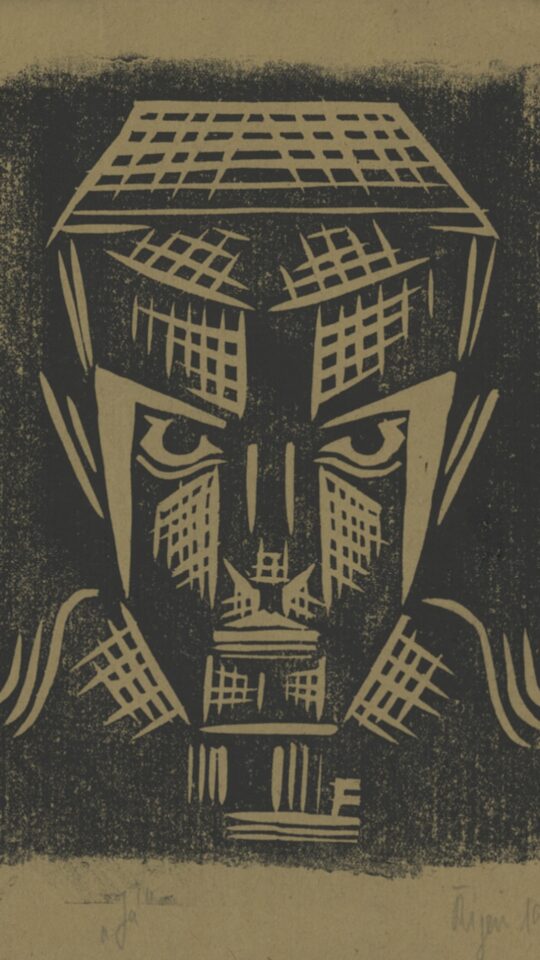

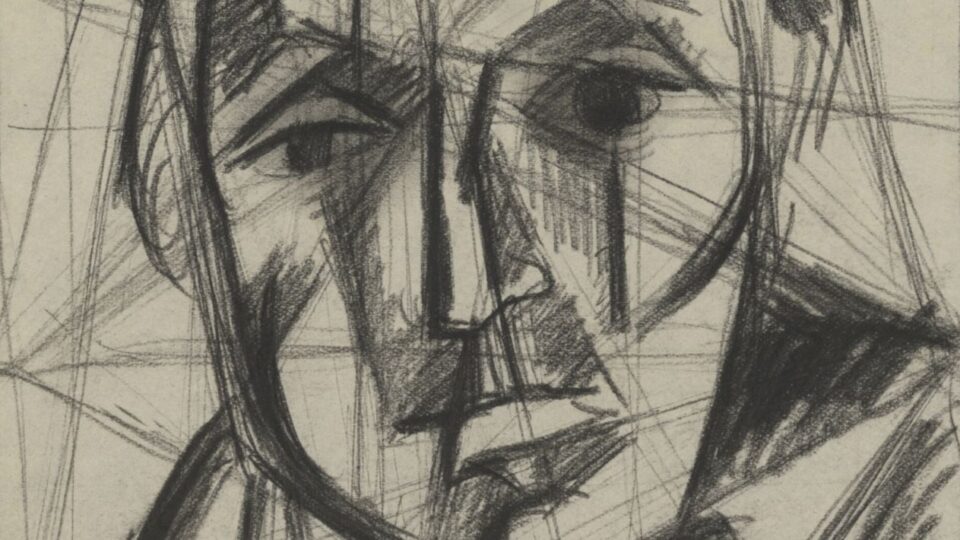

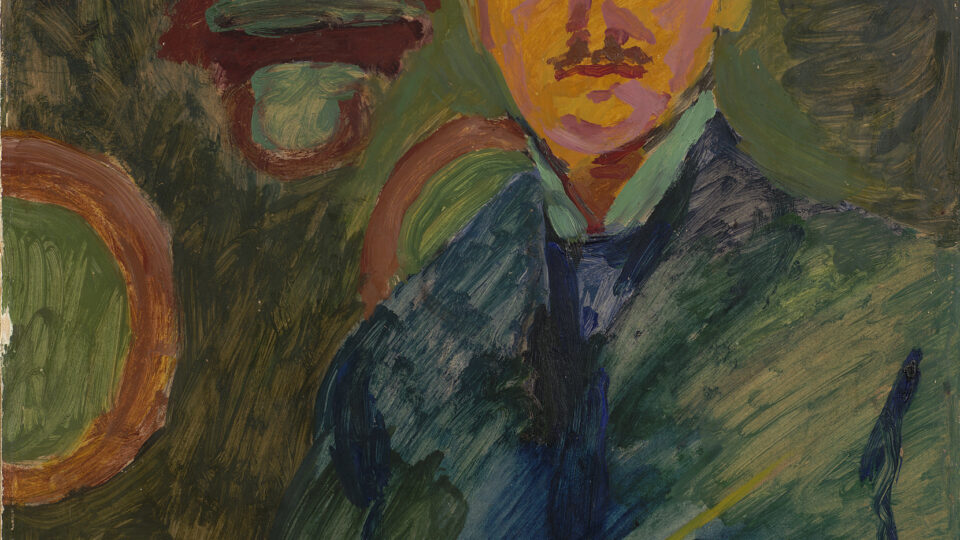

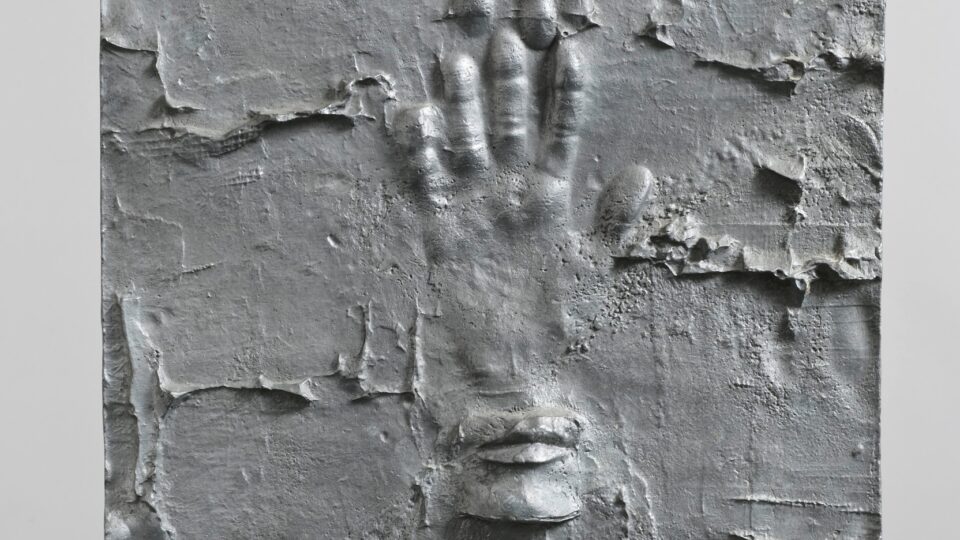

Why, then, have modern artists sat before the mirror? Their motivations usually transcend attempts at producing a most faithful rendition of their likeness since this exclusive position was successfully taken over by photography after its triumphant conquest at the turn of the 20th century. With their works, artists demonstrated their exclusivity, how they wished to be seen and how much they felt themselves to be a part of society – or, conversely, how much they sought to break away from it. They depicted themselves in the act of painting, holding their paintbrushes, though also in moments of melancholy and sorrow. They also portrayed themselves with a focus on elegance and charm, nonchalantly holding a cigarette or a pipe while gazing determinedly at the viewer. New artistic and formal techniques transformed their faces, which manifested new ways of seeing and perceiving while becoming the subject of experimentation. They depicted themselves lost in thought, introspective and meditating upon their own likeness; they also showed their face transformed into a mask that protects and hides the true form of its wearer. They often identified with literary and historical figures whose mental disposition, work and lives represented impressive parallels to the artist’s own life and social status. The last decade of the 20th century and the start of the new millennium were characterised by political change, a relaxation of social customs and the emergence of new themes and strategies such as conceptual approaches to one’s likeness and history, to the body, to physicality and sex, to the question of observing the individual, voyeurism and the search for identity and gender. Art as an integral part of visual culture has become an important part of public space and has begun to respond to the advertising industry, politics, the environment and popular culture. Artistic interventions often overlap with social and political activism.

The broad range of approaches spanning more than a century, combined with contemporary visual culture’s invasion of our lives, leads us to wonder how exactly we should view the genre of the self-portrait in this era of the narcissistic culture of the selfie. Do self-portraits say more about the artist or about the time in which they were made? How did artists wish to be seen and perceived by society in the turbulent 20th century? What does their stylisation in a self-portrait tell us about their character, beliefs and way of thinking? The answers to many of these questions can be found in the works of Emil Filla, Bohumil Kubišta, František Kobliha, Vratislav Nechleba, Dana Puchnarová, Václav Stratil, Milena Dopitová and Jolana Havelková from the GASK collection.

Vanda Skálová